Abstract

In this paper, we propose a Transfer Learning approach for artwork attribution investigating the importance of the artist’s signature. We consider the AlexNet Convolutional Neural Network and different fully connected layers after fc7. Three architectures are compared for authenticating paintings from Monet and classifying other artworks into the “Not‑Monet” class. We considered paintings with a similar style and artist’s signature to Monet’s, as well as paintings with a very different style and signature. We assess the model’s performance on images with the artist’s signature extracted from the artwork, as well as on images of its near background not containing the signature. Results demonstrate the importance of considering the artist’s signature for art attribution, reaching a classification rate of 85.6% against 82% on images without signature. The analysis of the obtained feature maps highlights the power of Transfer Learning in extracting high‑level features that simultaneously capture information from the artist’s signature and the artist’s style.

Keywords: Transfer Learning, AlexNet model, handwritten signature images, background images, artwork authentication, feature maps.

I. Introduction

Artwork authentication is a complex and multifaceted process of great importance to academic art history and the commercial art market. Determining authenticity and authorship is an essential prerequisite for sales and acquisitions, and is mainly carried out through visual inspection by experts. This traditional methodology is time‑consuming and subjective. Advances in high‑resolution imaging and machine learning make AI promising for automatic decision‑aid in authentication.

Few works address automatic classification for artwork attribution. Prior studies explored CNNs and Transfer Learning for feature extraction and artist attribution on whole‑painting images. However, the artist’s handwritten signature—when present—can carry valuable information and is widely used in handwriting forensics. Here, we investigate the contribution of the artist’s signature for attribution using Monet as a case study, comparing: (i) images including the signature; and (ii) images from the near background area without the signature.

II. Material and methods

A. Database collection

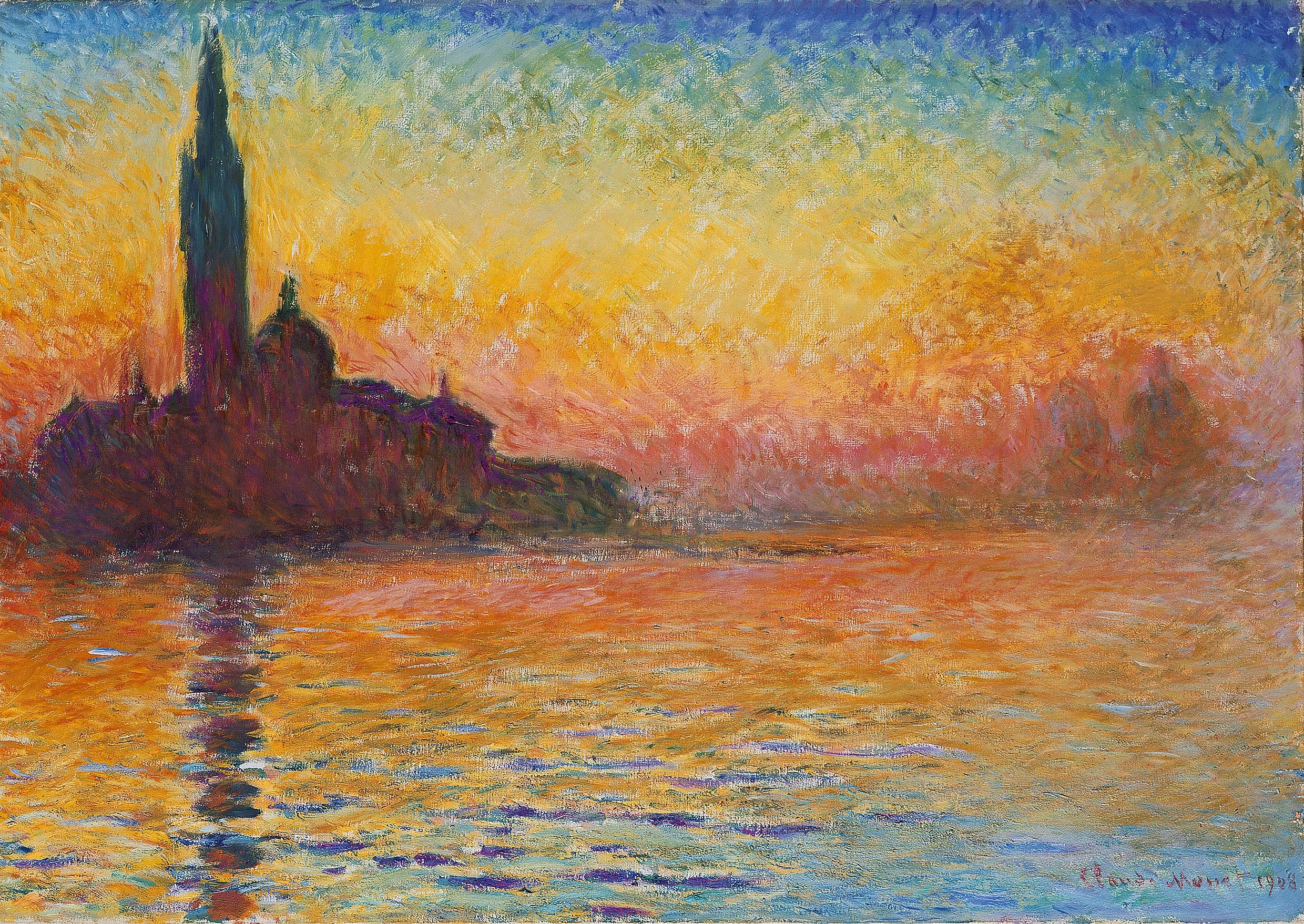

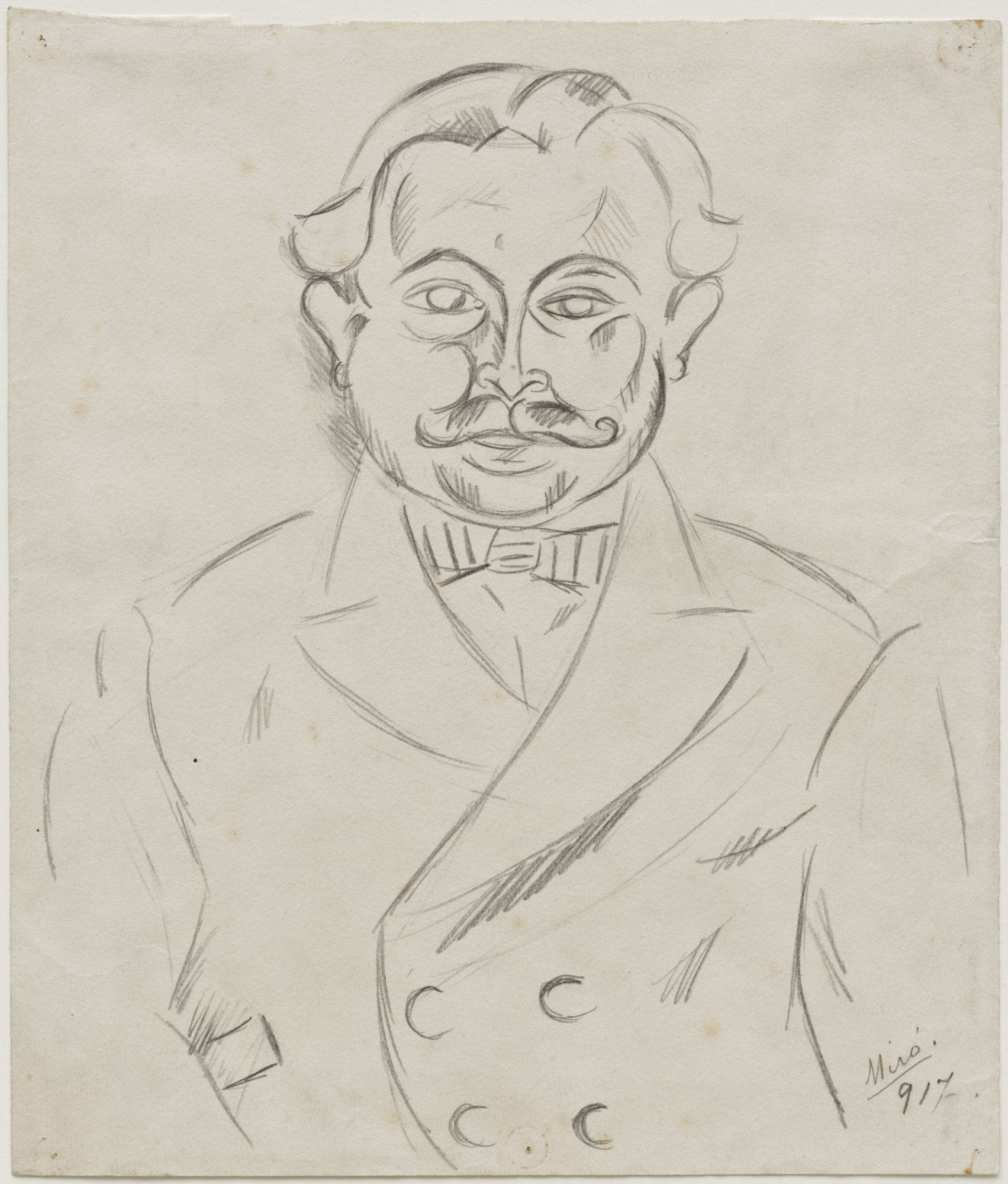

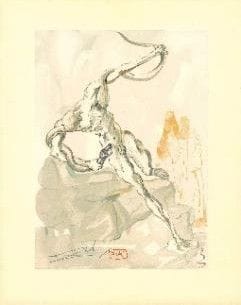

We constructed a dataset of 500 signed artworks from public domain sources (Google Arts and Culture, National Gallery of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Munch Museum, Musée d’Orsay, among others). The dataset includes 250 Monet paintings (“Monet” class) and 250 paintings from other artists (“Not‑Monet” class), including Manet (92), Sisley (51), Klimt (12), Munch (75), Miró (8), and Dalí (12).

B. Creation of two data subsets

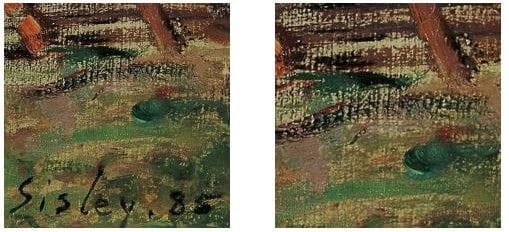

To evaluate the contribution of the signature, we study two cases using 227×227 RGB crops: (1) images including the artist’s handwritten signature; and (2) images from the near background without the signature, matched in texture/color to the signature background.

C. Transfer Learning with AlexNet

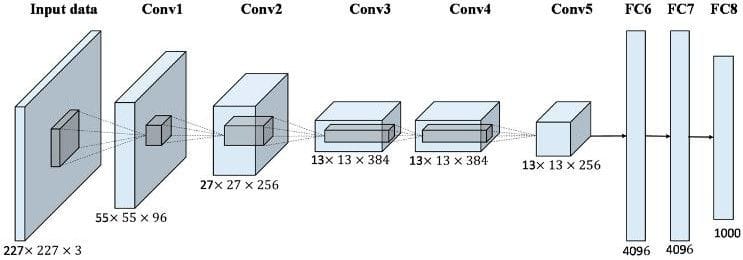

We perform Transfer Learning with AlexNet pre‑trained on ImageNet. AlexNet contains five convolutional layers followed by three fully connected layers. We extract 4096‑dimensional feature vectors from layer fc7.

We study three classifier heads between fc7 and the 2‑unit output (Monet vs Not‑Monet):

- Architecture1: one hidden layer (1024)

- Architecture2: two hidden layers (1024, 512)

- Architecture3: three hidden layers (2048, 1024, 512)

Only the additional fully connected layers are trained.

D. Performance assessment

We use 3‑fold cross‑validation. Hyper‑parameters (epochs, initial learning rate, batch size, step size, gamma) are optimized with grid search on training/validation sets only. We report averages over test sets.

III. Experimental results

A. Performance on images with signature

Architecture2 yields the best classification rate on images with signature.

| Architecture | Monet correctly classified |

|---|---|

| Architecture1 | 81.6% |

| Architecture2 | 88.0% |

| Architecture3 | 83.6% |

Per‑artist results with signature (Architecture2):

| Class | Correct (count) | Incorrect (count) |

|---|---|---|

| Monet (n=250) | 220 (88%) | 30 (12%) |

| Manet (n=92) | 79 (85.87%) | 13 (14.13%) |

| Sisley (n=51) | 41 (80.4%) | 10 (19.6%) |

| Klimt (n=12) | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) |

| Munch (n=75) | 69 (92%) | 6 (8%) |

| Miró (n=8) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dalí (n=12) | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

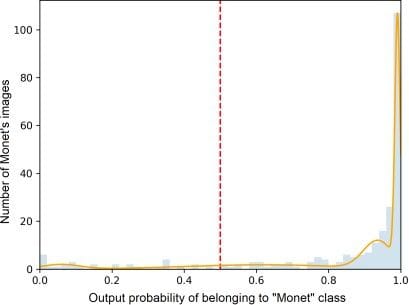

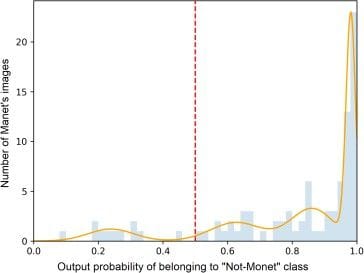

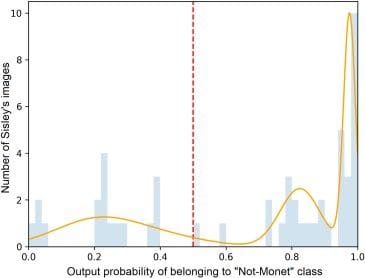

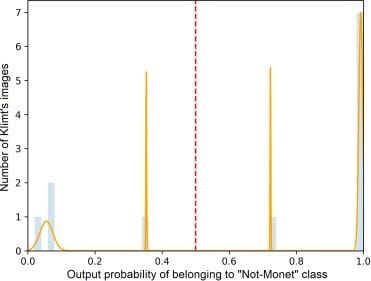

We observe that the highest classification errors correspond to images from Manet, Sisley and Klimt. This is confirmed by the relatively low probability values of being classified in the “Not‑Monet” class, as shown in Fig. 7 for these three artists. The model faces particular challenges with these impressionist and post‑impressionist painters whose artistic styles share similarities with Monet’s work.

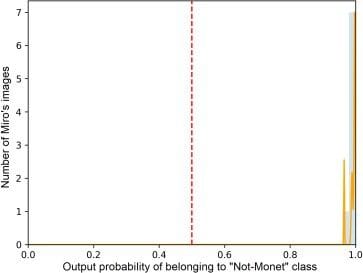

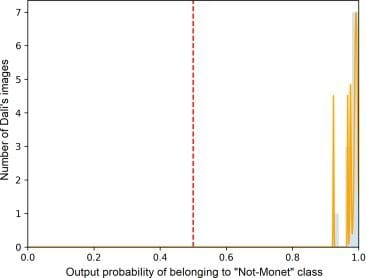

On the other hand, Miró’s and Dalí’s images are all correctly classified as “Not‑Monet”, with high probability values displayed in Fig. 8. These artists employ distinctly different artistic styles and signing tools compared to Monet, making their works easily distinguishable. Similarly, Munch’s images are in majority correctly classified as “Not‑Monet” with high probability scores.

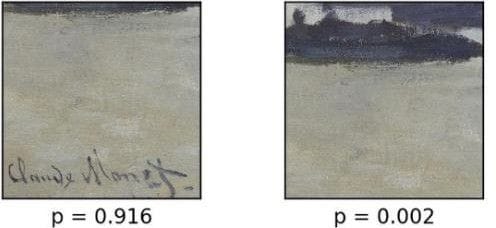

Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 display examples of Monet’s images that are, respectively, correctly and wrongly classified. Their probability of belonging to the “Monet” class and “Not‑Monet” class is also reported in the figures’ captions.

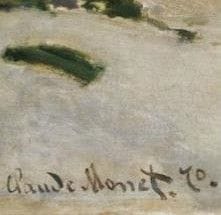

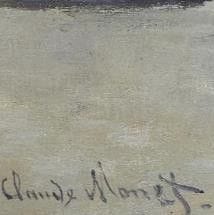

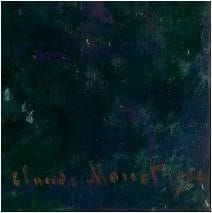

We observe that Monet’s images with high probability values show a pronounced contrast between the signature and its background (Fig. 10a and Fig. 10b). The signature is completely distinguishable and legible in these cases. For the Monet’s image in Fig. 10c, it is clearly more difficult to distinguish the signature from the background, which is highly textured. The signature was affixed in similar colors as the background and is actually integrated in the painting. Despite these visual characteristics, the model was able to correctly classify this image, though with a lower probability value compared to images in Fig. 10a and Fig. 10b.

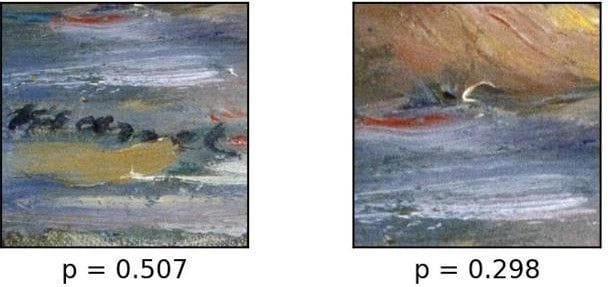

On the other hand, the model was unable to correctly classify some Monet’s images, as those shown in Fig. 11. In Fig. 11a, the model faces the same problem encountered in Fig. 10c: the signature is not distinct from the background since they share similar colors. In Fig. 11b, we observe a lack of contrast between the signature and its very dark background. Finally, the signature in Fig. 11c is very different from the former Monet’s signatures displayed: although well contrasted, it suffers from a lack of legibility due to its coarse trace; besides it is slanted to the right.

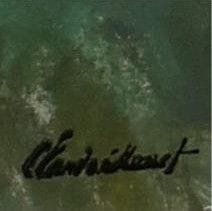

Fig. 12 shows examples of Manet’s and Sisley’s images wrongly classified. In Fig. 12a, the signature is hardly distinguishable from the background, which explains the classification error. For the images in Fig. 12b and Fig. 12c, Sisley’s signature was affixed on a highly textured background of similar colors. Moreover, both backgrounds show a similar style to some Monet’s paintings, as illustrated in Fig. 13.

B. Comparison: with vs without signature

Correct classification rates (Architecture2):

| Case | Monet correctly classified | Not‑Monet correctly classified |

|---|---|---|

| With signature | 88.0% | 87.2% |

| Without signature | 86.0% | 78.0% |

Including the signature improves overall accuracy from 82.0% (without) to 85.6% (with). The largest degradation without signatures occurs on Sisley (from 80.4% correct to 35.3% correct for Not‑Monet), suggesting the signature provides discriminative authorship cues when backgrounds are highly textured and Monet‑like.

Per‑artist results without signature (Architecture2):

| Class | Monet | Not‑Monet |

|---|---|---|

| Monet (n=250) | 215 (86%) | 35 (14%) |

| Manet (n=92) | 15 (16.3%) | 77 (83.7%) |

| Sisley (n=51) | 33 (64.7%) | 18 (35.3%) |

| Klimt (n=12) | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) |

| Munch (n=75) | 4 (5.33%) | 71 (94.67%) |

| Miró (n=8) | 0 (0%) | 8 (100%) |

| Dalí (n=12) | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) |

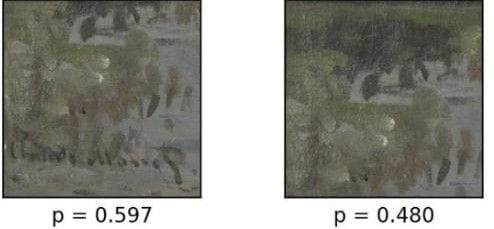

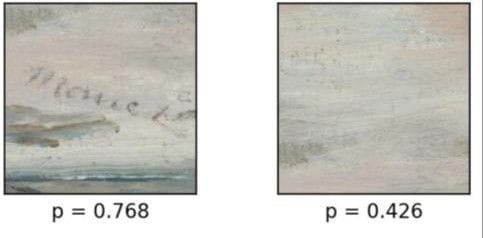

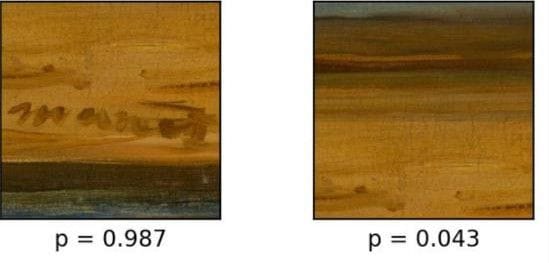

This result indicates the importance of the signature for artwork authentication. This is confirmed by the examples displayed in Fig. 15: the output probability of belonging to the “Monet” class is degraded when the signature is not considered. This is also illustrated in Fig. 16 for the “Not-Monet” class.

C. Feature map visualization

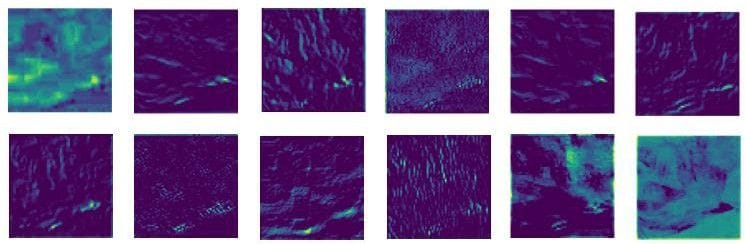

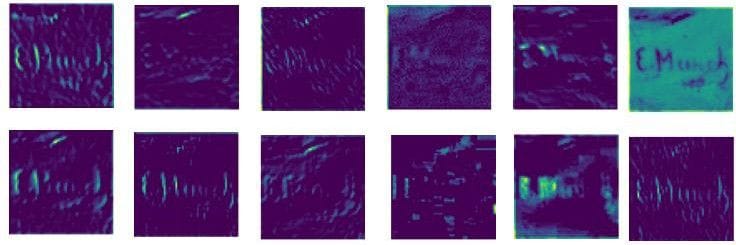

We visualize feature maps to better understand the extracted representations with and without signatures, showing that filters capture both background textures and signature strokes when present.

We see in Fig. 18 that the extracted feature maps include different patterns from the background. Some correspond to coarse textural features and other capture fine details of the image background. In Fig. 19, some feature maps extract high- level features from the background, whereas other concentrate on the characteristics of the artist’s signature.

This double high-level feature extraction of the artwork fusing information from the background and from the artist’s signature, leads to a more accurate classification performance. This way, we conclude that our model allows capturing information simultaneously from the artist’s signature and the artist’s style.

IV. Conclusion and perspectives

On a dataset of 250 Monet and 250 other signed paintings, we studied AlexNet‑based Transfer Learning with three classifier heads. Architecture2 (1024→512) performed best, reaching 88% correct for Monet signature‑images and 87.2% for Not‑Monet signature‑images. Using background‑only crops reduces accuracy to 82%, versus 85.6% when including the signature. Errors concentrate on Manet and Sisley when signatures are absent, likely due to Monet‑like textured backgrounds. Feature‑map analyses indicate complementary high‑level features from both background and signature, supporting the value of considering signatures for authentication. Future work includes leveraging the whole painting or multiple regions of interest and exploring alternative backbones and classifiers.

References

- Koziczak, A. The form of painter’s signature and its suitability for the assessment of the authenticity of paintings. Trames Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences. 21(4):403, 2017. doi: 10.3176/tr.2017.4.07

- Bensimon, P. L’expertise des signatures en matière de faux tableaux. Revue Internationale de Police Criminelle 457, 28–30, 1996.

- Matthew, L.C. The Painter’s Presence: Signatures in Venetian Renaissance Pictures. The Art Bulletin 80(4), 616–648, 1998.

- Ugail, H., et al. Deep transfer learning for visual analysis and attribution of paintings by Raphael. Heritage Science 11, 268 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01094-0

- van Noord, N., et al. Toward discovery of the artist’s style: Learning to recognize artists by their artworks. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 32(4):46–54, 2015.

- Mensink, T., van Gemert, J. The Rijksmuseum challenge: museum‑centered visual recognition. ICMR, 2–5, 2014.

- van Noord, N., et al. Learning scale‑variant and scale‑invariant features for deep image classification. Pattern Recognition, 61:583–592, 2017.

- Schaerf, et al. Art authentication with vision transformers. Neural Computing & Applications (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08864-8

- Morris, R.N. Forensic handwriting identification: fundamental concepts and principles. Academic Press, 2000.

- Kelly, J.S., et al. Scientific examination of questioned documents. CRC Press, 2006.

- Li, Z., Liu, X. An examination of handwritten signatures forged using photosensitive signature stamp. Forensic Sci Res. 6(2):168–182, 2021. doi:10.1080/20961790.2021.1898755

- Kam, M., Gummadidala, K., Fielding, G., Conn, R. Signature authentication by forensic document examiners. J. Forensic Sci. 46, 884–888, 2001.

- Sita, J., Found, B., Rogers, D.K. Forensic handwriting examiners’ expertise for signature comparison. J. Forensic Sci. 47, 1117–1124, 2002.

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., Hinton, G. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. NeurIPS, 1097–1105, 2012.